Cover Story: Two Centuries of Caring

Two hundred years ago, care for the mentally ill dramatically changed with the founding of the Hartford Retreat for the Insane, now known as the Institute of Living (IOL).

The institute’s legacy will be highlighted by a two-year anniversary celebration commemorating its 1822 founding and 1824 opening.

Here, we take a peek at the rich history of the IOL, suggest a visit to its verdant grounds planned by internationally-acclaimed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, and, with today’s leaders, look to a future marked by research and ever-expanding treatment options.

—Susan McDonald

Institute of Living Revolutionized Care for Mentally Ill

Susan McDonald

Founded in 1822 and opened on April 4, 1824, the Hartford Retreat for the Insane, now known as the Institute of Living, dramatically changing the delivery of psychiatric care.

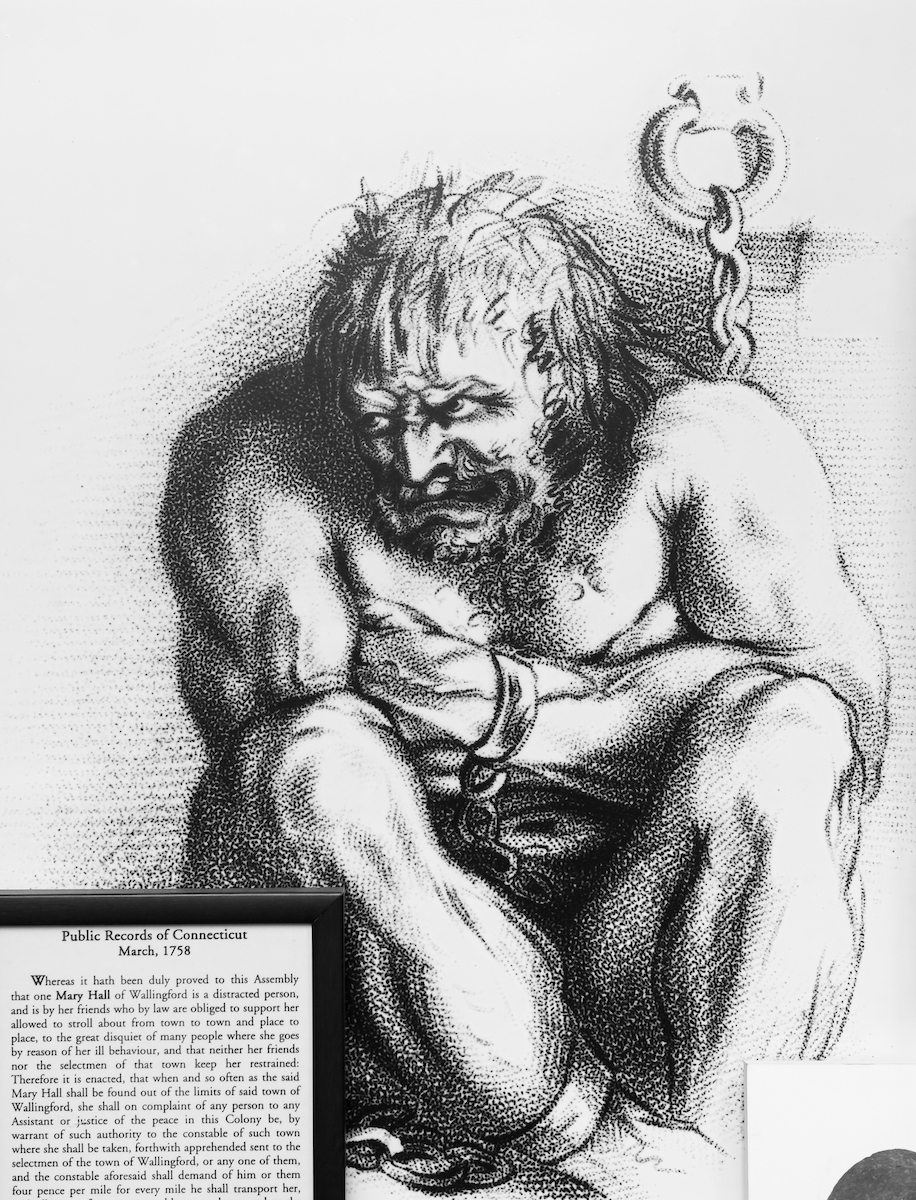

“Before that, people with mental illness had been locked away in prisons or poor houses. There was no perception of mental disorder as an illness, rather the signs and symptoms were considered evidence of criminal behavior or demonic possession,” said Dr. Harold “Hank” Schwartz, who was Psychiatrist-in-Chief of the IOL for 29 years before stepping down from leadership in 2018.

It was certainly a different time, with very little resemblance to the behavioral health landscape of today.

The Institute of Living (IOL) was among only four facilities of its kind in the nation. According to historical documents, it was capable of accommodating 40 to 60 patients and patients were segregated by “sex, nature of disease, habits of life and the wishes of their friends.”

The weekly cost of care was $3 for Connecticut residents, $4 for those from out of state and $10 to $12 for a suite with an exclusive personal attendant.

Revolutionary Care

From the very first patients – a 36-year-old man suffering from “fanaticism” and a 26-year-old woman who had “broken down from overtaxing the intellect with difficult studies” – the IOL changed the treatment and care of the mentally ill in dramatic and progressive ways, Dr. Schwartz said.

“While both our understanding of mental illness and our ability to treat it have significantly advanced since then…many of the founding principles that governed the practices of this remarkable institution in its earliest years remain relevant today,” Schwartz wrote in the foreword of Mad Yankees: The Hartford Retreat for the Insane and Nineteenth-Century Psychiatry by Lawrence B. Goodheart.

The revolution was sparked by Dr. Eli Todd, the institution’s first superintendent who became interested in mental illness after caring for a sister who suffered from depression and eventually committed suicide. An empiricist, he championed the concept of mental illness as a disease and promoted the philosophy of moral treatment focused on patients’ individual needs.

Such ideals were followed by IOL physicians at a time when the field of medicine was distinguishing itself from religion. In fact, the IOL was the first in the country founded with donations from a state medical society.

Dr. Amariah Brigham, the third superintendent who founded the country’s first psychiatric journal (now the American Journal of Psychiatry), was one of the first neuroscientists and “the father” of social psychiatry, laying the groundwork for what is now called the “biopsychosocial model” of care. He conducted brain autopsies to correlate symptoms with gross anatomical changes in the brain. Analogies can be easily drawn to the many investigations underway today using 3T MRI scanners in the IOL’s Olin Neuropsychiatry Center.

The institution experienced waves of immigration during the 19th century, with poor German, Irish and other immigrants stressing its ability to care for those unable to pay for services until the state established public hospitals in the late 1860s, providing the first distinction between public and private care.

Periods of success and struggle marked the end of one century and the beginning of the next. But, in 1867, the grounds of the facility received a huge boost when renowned landscape designer and Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted created a park-like environment that featured a wide variety of special specimen trees still attracting visitors today.

More innovation and evolution was in store for the IOL with the naming of Dr. C. Charles Burlingame as superintendent in 1939. His vision was for the facility to become one third hospital, one third university/educational environment and one third resort. While continuing to ensure quality moral care for patients, some of whom were hospitalized for years, he oversaw a tremendous expansion of services designed to improve their health and keep them comfortable. This included adding residential cottages, a nine-hole golf course, indoor and outdoor pools and tennis courts, all of which are gone today.

Dr. Burlingame added an educational program for patients with lectures and workshops on homemaking and woodworking. Groups of patients were taken to a nearby lake each summer and staff took others on New York City shopping trips.

During that time, various Hollywood stars and politicians came to the IOL for treatment, Dr. Schwartz noted.

“Whatever the people wanted, he tried to provide it for them,” he said of Dr. Burlingame, who also elicited staff ideas with a suggestion box. One of the most notable ideas was the new name for the facility in the early 1940s.

Dr. Burlingame also expanded research at the IOL with the construction of a dedicated building featuring state-of-the-art equipment.

The expansion of programming continued through the 1980s. Dr. Francis Braceland, for example, oversaw the creation of the Professionals Program to help professionally employed people address their illness without losing their job.

The advent of managed healthcare in the 1980s heralded Dr. Schwartz’s arrival from his post as chair of psychiatry at Hartford Hospital.

“There was practically a wall down Retreat Avenue separating the IOL and Hartford Hospital. We shared very little until that point,” he remembered.

In the late 1980s, the IOL staffed 450 beds with many patients staying for months and years until managed care forced the facility to downsize an astonishing nine times in just three years. By the early 1990s, the IOL was reduced to 150 beds and had an average length of stay of 28 days.

“Managed care eviscerated psychiatric hospitals in America and every hospital had to find its own solution to the challenge,” Dr. Schwartz said, adding that the solution at the IOL was consolidating with Hartford Hospital

The IOL and Hartford Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry merged in 1994 and the next year saw a blending of programs, staffs, ideals and goals.

“It was the hardest working year I’ve ever put in in my life,” Schwartz said. “I worked long days to get it right and I think we did get it right!”

As a result of the merger, the IOL could accept Medicaid patients, something private psychiatric hospitals in the United States cannot do.

“Until then, we really didn’t treat the community around us. Today, more than one third of the patients at the IOL are on Medicaid and we are very much focused on our community,” he said.

Under him, new programs such as the Schizophrenia Rehabilitation Program (focusing on cognitive rehabilitation), Anxiety Disorders Center, Early Psychosis Program and LGBTQ offerings, among many others, reshaped the IOL’s clinical landscape. Existing research programs were reinvigorated and new ones, like Olin, were established along with the reestablishment of independent residency programs.

Looking Ahead

Dr. Harold Schwartz, Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Institute of Living and Dr. John Santopietro, Physician-in-Chief for the Behavioral Health Network

Dr. Harold Schwartz, Psychiatrist-in-Chief at the Institute of Living and Dr. John Santopietro, Physician-in-Chief for the Behavioral Health Network

Dr. Schwartz entered semi-retirement in 2018 and Dr. John Santopietro was named the first physician-in-chief of the Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network, a role which now serves to link medical leadership across the system and tie the IOL more closely to Natchaug Hospital and Rushford, as well as services at The Hospital of Central Connecticut, Charlotte Hungerford and Backus hospitals and MidState Medical Center.

“We have an abiding responsibility for the individual,” he began. “It sounds simple but it’s not. There’s stigma and the mentally ill are still often treated as non-persons, as ‘other.’ But, the IOL stands like a beacon for the dignity and humanity of people suffering with mental illness. It is also like an incubator – there has always been fertile soil here for ideas. People came with an idea, planted it in the soil and it grew.”

He mentions the Anxiety Disorders Center as an example of a suggestion, this time from Dr. David Tolin, that was fostered and flourished.

Looking at gaps in service, the IOL has created programs for peripartum mood disorders, different tracks for treatment of psychosis, services specifically for the LGBTQ community and a Family Resource Center that organizes about 150 activities each year.

It is an environment, Dr. Santopietro said, that naturally attracts such national initiatives as Zero Suicide, which was adapted slightly by IOL staff to include a Suicide Assessment Model to help people assess an individual’s risk for suicide.

The IOL is focused on patient recovery, but also supporting people when they leave. The Schizophrenia Rehabilitation Center, for example, helps people live in the community, leading to a lower mortality rate in this population. The Vocational Rehabilitation Program provides job training skills in the IOL gift shop, greenhouse and cafeteria so patients can transition successfully to a job in the community.

Looking ahead, Dr. Santopietro said there is excitement and a tremendous sense of responsibility to perpetuate the reputation of care and progressive ideology at the IOL. He described the following as drivers for the near future:

– Genetic testing, one of Dr. Godfrey Pearlson’s research topics at the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, includes identifying biomarkers to help define diseases and the best medications to treat them for more personalized treatment.

– Increased integration of psychiatric care into the broader Hartford HealthCare system. Dr. Santopietro has experience implementing mental health care in primary care practices and envisioned the same transition locally. The Medication-Assisted Treatment Close to Home (MATCH) program for opioid users, he said, can be easily applied in a primary care setting or with cardiac surgeons treating drug users.

He also talked of expanding the health psychology fellowship that trains physicians in a range of medical areas – sleep medicine, orthopedics, headache, epilepsy, movement disorders, neuropsychology and heart transplant – across the system.

– Maintain the practice of moral treatment, which Dr. Santopietro called the facility’s “clinical soul.”

– Develop a provider wellness initiative at the system level that promotes healing activities in place at the IOL.

Research Leads the March Forward

Susan McDonald

Left: Dr. Godfrey Pearlson is director of the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center at the Institute of Living.

Right: Dr. Jimmy Choi investigates how the movement of a person’s pupils can provide a unique connection to psychosis.

In the labs, offices and patient rooms across the Institute of Living campus, researchers perform cutting-edge work every day to help improve diagnosis and treatment of mental illness.

Three main hubs of research on the campus — the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center, Anxiety Disorders Center and Clinical Trials Unit — work with government, industry and private foundation funding totaling about $80.6 million since 2007.

Major research focuses at the IOL include:

• Psychosis, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorders

• Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

• Marijuana and driving

• Alcoholism

• Anxiety disorders

• Autism spectrum

• Depression

• Obesity

• Alzheimer’s disease

• Compulsive hoarding and Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

• Substance abuse

• Clinical trials of new medications

In Olin alone, there are six distinct research labs headed by individual investigators and their teams, many of whom tap the advanced technology on campus to test their hypotheses. Available technology includes structural and functional MRIs, diffusion tensor imaging and spectroscopy, plus fully-equipped electrophysiology and transcutaneous magnetic stimulation labs and a DNA repository, said Dr. Godfrey Pearlson, director of the Olin Center.

“What distinguishes us is the fact that we’re studying the neurobiology of serious mental illness, from the point of view of electrophysiology, functional and structural brain measurements and genetics, and combining those with epidemiology to try and translate those discoveries into new treatments,” he explained.

Recent discoveries by IOL researchers include:

• Biologic measures to classify psychotic illnesses into novel categories to connect patients with specific treatments.

• Intranasal ketamine to reverse treatment-resistant depression and suicidal thoughts.

• Distinct biological subtypes of ADHD.

• Use of brain response to alcohol cues in 18-year-olds to predict future dysfunctional drinking.

• Connection between heavy alcohol use in 18-year-olds over two years with brain hippocampal shrinkage, lower academic grades and lower memory scores.

• Identification of hoarding as a distinct disorder, not a variant of OCD.

• Biological overlap in the brain between Autism Spectrum Disorder and schizophrenia.

• Ability to predict 60 percent of 12-month bariatric surgical weight loss by examining pre-surgical brain patterns.

“We focus on translating research directly into patient care,” Dr. Pearlson said. “We embed our research organizations into our clinical programs, so the people delivering care are getting the information, learning about the developments as they’re happening.”

Addressing Myths, Minds and Medicine

Robin Stanley

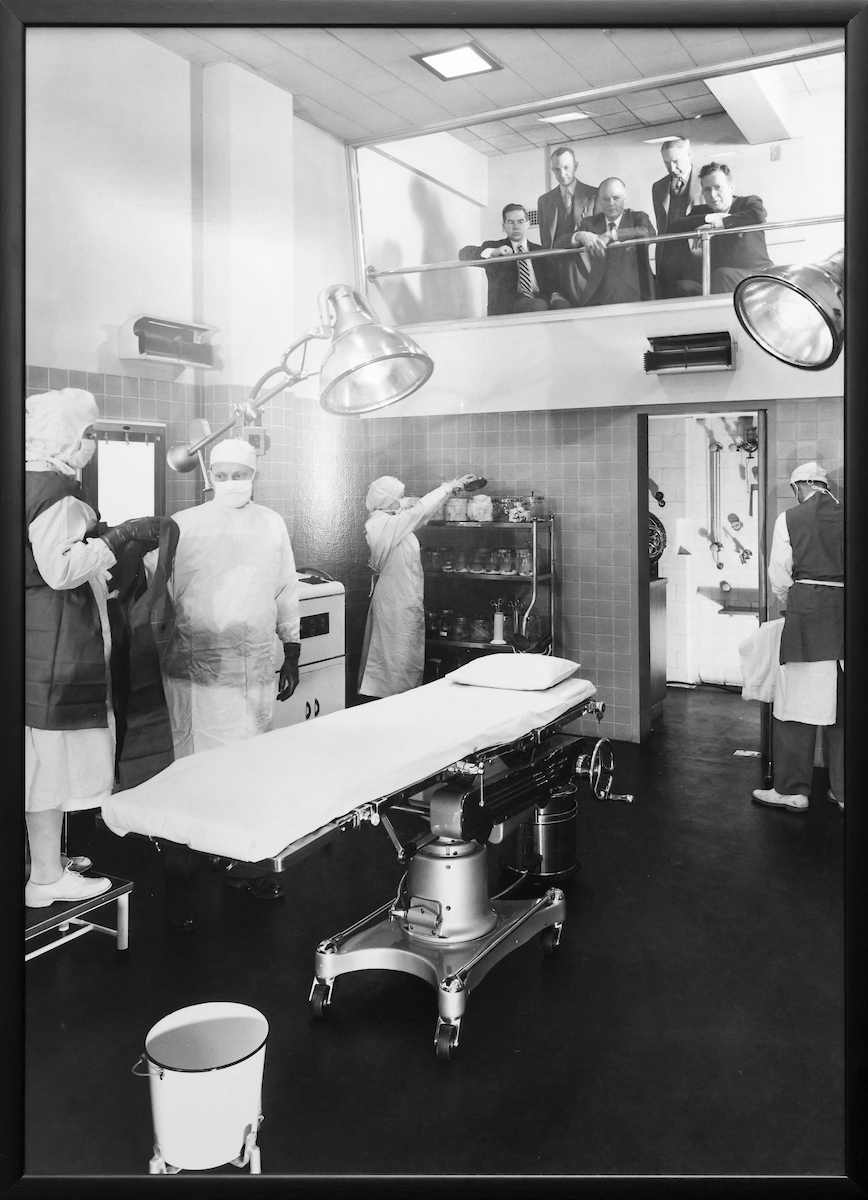

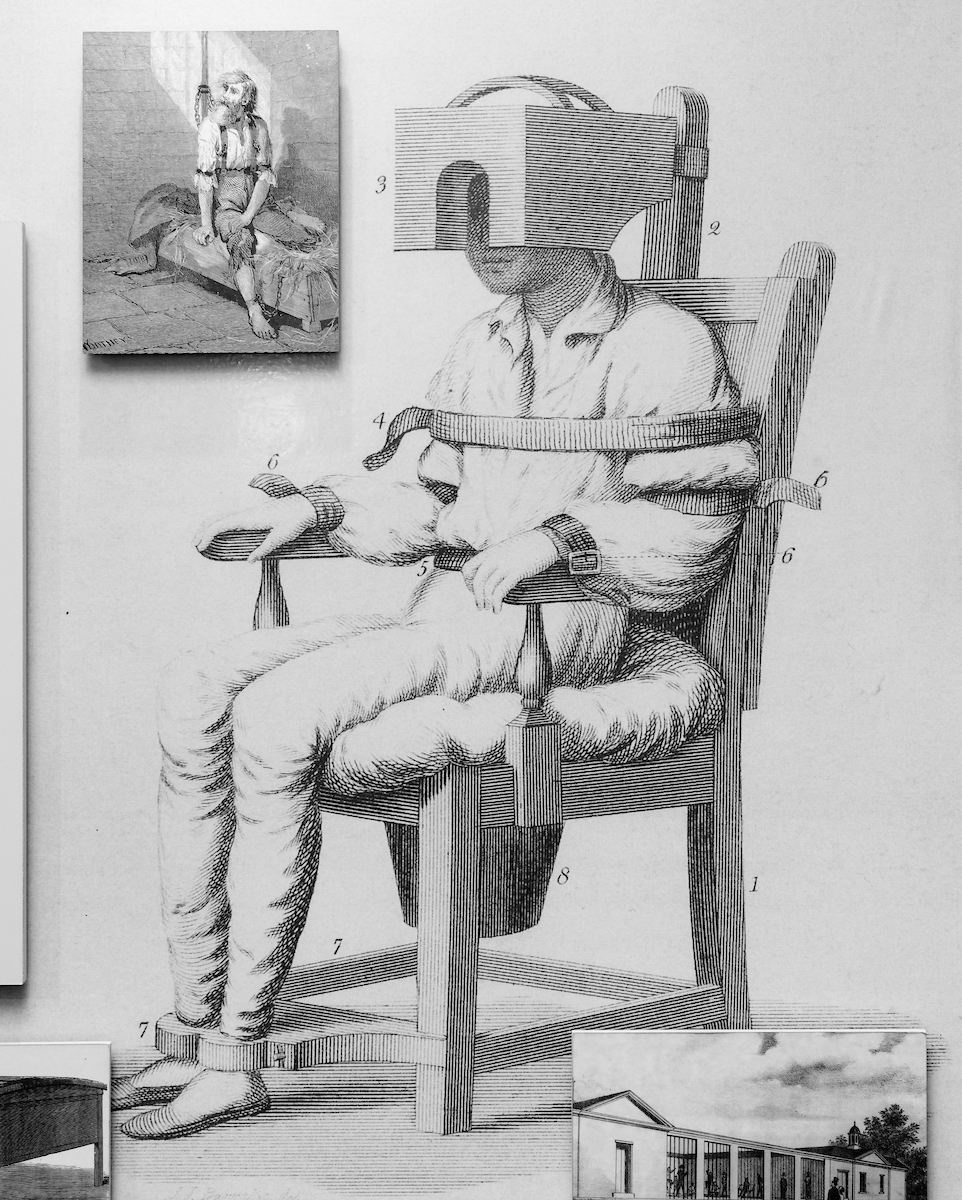

The Commons Building at the Institute of Living (IOL) contains a treasure trove of historical information on mental healthcare and the IOL, collated as the exhibit “Myths, Minds and Medicine: Two Centuries of Mental Healthcare” to celebrate the institute’s 175th anniversary in 1997.

The museum-quality exhibit, the brainchild of former Public Relations Director Lee Monroe, was the result of years of research by historians hired through a grant from the Connecticut Humanities Council.

Documents, artifacts, items of interest, letters and old photos were gathered from the IOL’s archives, attics, basements and offices to form the basis for the exhibit. Over the years, it has served as an educational resource to local schools and the community and helps dispel some of the myths and stereotypes around mental illness.

Twenty-five years later, the exhibit will be upgraded to reflect advances in mental healthcare and the technology used in its visual displays.

“Imagine state-of-the-art of museum exhibits 25 years ago, and the quality of some of the kinds of visual displays,” said Dr. Harold “Hank” Schwartz, IOL psychiatrist-in-chief emeritus. “In the version built 25 years ago, there was a TV screen where you could press a button and it played a video of patient activities. Well, it looks like a television screen 25 years ago, and today, of course, it’s all beautiful digital displays.”

Programs and treatments at the IOL also have evolved in the past 25 years.

“We are a major neuroimaging center,” Dr. Schwartz explained. “We had static images 25 years ago. Now, we will have digital video displays on contemporary monitors of neural imaging of the brain with explanations.”

Transcranial magnetic stimulation and esketamine, both treatments for major depressive disorder not offered 25 years ago, will also be featured.

“This exhibit is important for the IOL because of the pride we take in our own history and also learning about some of the stumbles,” Dr. Schwartz said. “Psychosurgery was not our proudest moment, for example, but we can’t just dismiss it. We need to talk about it and learn from it.”

“Myths, Minds and Medicine” is expected to reopen in the fall of 2022.

In addition to the exhibition reopening, the Commons Building façade is being renovated and renamed in honor of Dr. Schwartz’s distinguished leadership of the IOL.

Below: Artwork outlines mental healthcare’s evolution in the “Myths, Minds and Medicine” exhibit at the Institute of Living.

The Institute of Living Fun Facts

By Susan McDonald

The 200-year existence of the Institute of Living is full of interesting milestones, stories and advancements, including many that are quirky but lesser-known tidbits.

• Well-known 20th-century sculptor Frances Laughlin Wadsworth was one of 40 instructors brought into the IOL in the mid-1930s to teach art classes as part of the newly-established Department of Educational Therapy. The program, designed to teach psychiatric patients with something they might use when discharged, was a perfect fit for Wadsworth, who believed strongly in art education.

• The Staunton Williams Auditorium on campus was named after the president and CEO of Capewell Manufacturing Company, who served on the IOL board from 1951 to 1962, including as its 16th president.

• The Elizabeth Chapel was donated by Dr. Gurdon Wadsworth Russell in memory of his first wife. Built of Westerly granite in 1875, the chapel was designed by George Keller using a variation of the plan he created for Grace Episcopal Church in Windsor.

• The Netherwood Building was named for Stella Netherwood, a nurse and secretary at the IOL in the 1930s and 1940s. She was mentored by Anne Goodrich, the nursing superintendent at the time, but took many impactful decisions on committees and boards, including the Board of Directors, on her own. A1941 Hartford Courant article marveled that the IOL’s 50-car garage and motor pool, the largest privately owned in the city, was manned entirely by women led by Netherwood.

• The eight-story Burlingame Research Building, named for Dr. Charles Burlingame, superintendent of the IOL from 1951-1965, was designed by architect Irving W. Rutherford and built in 1948. The tower atop the building features the symbol of the Cadeceus, an ancient symbol believed to be a protector of physicians, on four sides, and is crowned by a gold dome. According to a Hartford Courant article in 1949, the fourth floor of the building was “unique in the hospital world” as it featured classrooms in which patients who had undergone surgery in operating rooms on the sixth floor regained social, vocational and recreational skills. Subjects included home economics, art and accounting.

• George Keller also designed White Hall, which was built on the IOL grounds in 1877 as a service building. It was used as a laundry, carpentry shop, vegetable cellar and coal storage vault. The IOL’s indoor swimming pool and squash courts were later housed there. When those were closed, the building was vacant until being revived as home for the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center.

• The Connecticut Historic Buildings website has great facts about the structures on the IOL campus.

• Visit the IOL in the 1960s through photos archived by JSTOR .

• Architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed the IOL grounds, believed in the healing powers of nature. He wrote, “The enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it, tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration of the whole system.”

• Before changing the name from the Hartford Retreat for the Insane to the Institute of Living in 1943, the facility was known as the Neuro- Psychiatric Institute of the Hartford Retreat.

• Mid-century patients had access to a fleet of chauffeur-driven Packards, Lincolns and Cadillacs for shopping or short day trips.

• Plug “Institute of Living” into the search engine on the Connecticut Historical Society website and you’ll find a wealth of cool information.

• Ground was broken on April 24, 1967 on the Gengras Adult Outpatient Clinic, named for E. Clayton Gengras, a local car dealer and self-made millionaire who was on the IOL board. The building replaced Bidwell Cottage and Jennings Hall, which were demolished.

• Check out Dr. Hank Schwartz give an overview of the IOL mission here.

Faces of the Institute of Living

Susan McDonald

Just a few of the faces that have made IOL what it is today!

Top Row, Left to Right: Dr. Javeed Sukhera, Dr. Francis Braceland, Annie Goodrich, RN, Dr. Hank Schwartz

Bottom Row, Left to Right: Dr. Silas Fuller, Dr. John Santopietro, Dr. C. Charles Burlingame, Dr. Amariah Brigham

Special thanks to Lori Hayes, library assistant in the Hartford Hospital/IOL archives, for her help with researching the biographical information.

The IOL history is rich with influential people who advocated for the humane care of the mentally ill. Here are a few immortalized on buildings and others who made their mark on the institution.

• Eli Todd. The IOL’s first superintendent, serving from 1823 to 1833, became interested in mental illness after caring for a sister who suffered from depression and eventually committed suicide. He championed the concept of mental illness as a disease and promoted the philosophy of moral treatment focused on patients’ individual needs, an approach known as “moral treatment.” “The great design of moral management,” he said, “is to bring those faculties which yet remain sound to bear upon those which are diseased.”

• Gideon Tomlinson, namesake of the Tomlinson Cottage, was a lawyer and former state representative who served as president of the Institute from 1827 to 1836. He left to serve as the state’s 25th governor, resigning after being appointed to the U.S. Senate. He is also known as one of the first railroad presidents in the nation, at the helm of the Housatonic Railroad Company.

• Silas Fuller. Appointed physician and superintendent in 1833, he was a native of Columbia, CT, and had served as a surgeon in the U.S. Army. He served at the facility until 1840.

• Amariah Brigham. Third superintendent and founder of the country’s first psychiatric journal (now the American Journal of Psychiatry), he was among the first neuroscientists and “the father” of social psychiatry, laying the groundwork for what is now called the “biopsychosocial model” of care. He helped shepherd the IOL from a custodial to a curative institution.

• Dr. John Butler. Presiding over a large influx of patients, many who could not pay for services, he served as superintendent for 30 years beginning in 1843. Before the state hospital was built to ease the overcrowding, he instituted key upgrades to the property including shifting from fireplaces to a boiler for heat, introducing as lighting to brighten rooms and hallways, and adding wings to accommodate patients.

• William Buckingham, president of the IOL from 1868 to 1875, owned a dry goods store in Norwich, where he served several terms as mayor from the Whig party. He was also manager and treasurer of Haywood Rubber Company, which he helped form. From 1858 to 1866, he served as governor, managing the economic panic from the Civil War and using his own money to finance the state’s war efforts. He also served in the U.S. Senate from1869 to his death in 1875. Buckingham Hall is named for him.

• Henry Putnam Sterns. After being named superintendent in 1874, he requested time to travel in Europe to familiarize himself with European medicine and, particularly, the way doctors their treated the insane. The Civil War veteran, who saw action at Bull Run, developed an interest in helping people with “mental disease,” possibly as a result of his military work. Before stepping down in 1905, he oversaw the expansion of patient rooms to meet increased demand and the introduction of modern amenities like radiators.

• C. Charles Burlingame. Named superintendent in 1939, he focused on transforming the IOL to equal parts hospital, university/educational environment and resort to appeal to the wealthy. While this meant adding indoor and outdoor pools, tennis courts and a nine-hole golf course, he’s also credited with expanding research with a dedicated building featuring state-of-the-art equipment.

• Francis Braceland. As chief psychiatrist of the IOL from 1951 to 1965, the prominent wartime physician is credited with shifting the facility’s reputation from posh sanitarium for the rich and famous to a highly-respected psychiatric hospital. He oversaw creation of the IOL Professionals Program to help professionally-employed people address their illness without losing their job.

• Dr. John Donnelly. An English native arrived at the IOL in 1949 as a psychiatrist, and rose through the ranks to become medical director in 1956 and, in 1965, psychiatrist-in-chief and chief executive officer. He served until retirement in 1979. He was active on a national level as well, serving as co-chair of an American Psychiatric Association committee investigating concerns that Russia was using psychiatry as punishment.

• Dr. Harold “Hank” Schwartz. Arriving in the 1980s from Hartford Hospital, and working for 29 years as psychiatrist-in-chief, he is credited with reshaping its clinical landscape with the creation of such programs as the Schizophrenia Rehabilitation Program (focusing on cognitive rehabilitation), Anxiety Disorders Center, Early Psychosis Program and LGBTQ offerings, among others. Existing research programs were reinvigorated and new ones, like Olin, were created along with the reestablishment of independent residency programs.

Leaders Look to Grow, Partner with Patients on Care

Susan McDonald

As the Institute of Living as it celebrates its past, its leaders are looking at the state of the world and the potential for the organization to lead into the future.

“We’re doubling down on the heart. We look regularly at where we are as a globe. Humanity needs us right now,” said Dr. John Santopietro, senior vice president, Hartford HealthCare, physician-in-chief of the Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network, which includes the IOL. “Depression rates are three times what they used to be. I’m worried about us if we keep going the way we’re going.”

Embracing positive change, is a vision he shares with Dr. Javeed Sukhera, chief of psychiatry at the IOL and chief of the Department of Psychiatry, Hartford Hospital.

“This place was founded on new ways of thinking that centers on the dignity of those we serve,” Dr. Sukhera said. “We are co-creating the future with patients, and will need to build systems that honor lived experience as expertise, embed patient voices in our work, and encourage people working here to bring their full humanity to everything they do.”

The steps to get there, he added, might be perceived by some as loss.

“Overall, health services have drifted toward a mindset that people who come in for help are somehow lacking something. This is a characterization we must reject. Instead, let’s emphasize that all of us have strengths and vulnerabilities, and the only way to heal is to work together,” Dr. Sukhera explained of the patient-provider partnership.

“People come in here not seeing their strengths, and we need to remind them that they are stronger than they know,” Dr. Santopietro added.

The evolution will involve tapping technology and research to provide the tools and skills patients need for success, while continuing to create services that meet the community’s needs. Recently, these have included services for peripartum mood disorders, different tracks for treatment of psychosis, services specifically for the LGBTQ community, a Family Resource Center that organizes about 150 activities a year, and modification of national initiatives like Zero Suicide to include a Suicide Assessment Model.

The work done on the campus continues in a supportive manner when patients leave. The Schizophrenia Rehabilitation Center, for example, helps people live in the community, lowering the mortality rate in this population. The Vocational Rehabilitation Program provides job training skills in the IOL gift shop, greenhouse and cafeteria to help patients transition successfully to jobs in the community.

“We are building our system to meet the challenge — IOL 2.0. Doing things based on the old game plan doesn’t work. When people call for help, it takes forever to get them in,” Dr. Santopietro said. “We don’t have the answers, but we will find them together.”

Where are we heading?

Susan McDonald

For two centuries, the Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network (BHN) — which includes the Institute of Living, Natchaug and Rushford at inpatient and ambulatory sites statewide — has connected children, teens and adults to a myriad of behavioral health and addiction services.

“Hartford HealthCare is sitting on one of the most comprehensive and strong behavioral health networks in the country,” said Dr. John Santopietro, BHN physician-in-chief. “With 3,000 colleagues and four campuses, we have more horsepower than any other hospital system in the nation.”

As the demand for services has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, the BHN has continued to grow and find ways to embed programs, services, technology and providers where they are needed most. Over the past year, new or expanded research and treatments that have garnered recognition includes:

• The Esketamine Treatment Center, where a nasal-spray form of the anesthesia medication ketamine for treatment-resistant depression.

• Research by the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center into the influence of marijuana on drivers and the impact of cannabis on memory in people ages 18-22.

• Expanded MATCH partnerships with local law enforcement and EMS to address the opioid crisis by offering opioid users addiction services instead of criminal punishment.

• A Professionals Program for employed individuals seeking support for emotional, psychiatric and addiction recovery issues.

In 2022, the BHN will continue to expand services with development of The Ridge Recovery Center, a 38,605-square-foot building in Willimantic that will be home to a new, state-of-the art treatment center for individuals with substance use disorder. More services are being added to facilities in Westport as well.

“We are growing, innovating and ready to meet the challenges,” Dr. Santopietro said.

The newest Behavioral Health Network location in Westport feeds the mission to bring expert care close to the people who need it.

Struggling with Wintery Darkness? Help is Here

Emily Perkins

Nearly 1 in 5 adults in the United States admit to struggling with their mental health, and the global pandemic, political unrest, remote learning, isolation and soaring unemployment in the past few years have heightened awareness of the need for more mental health services and programs in our country.

This time of year — with the colder temperatures and earlier nightfall — brings its own sort of mental health challenges. The lack of sunlight exposure can cause Seasonal Affective Disorder.

Dr. Ila Sabino from the Behavioral Health Network offers the following tips for keeping your mood up during the winter:

• Get sunlight when you can. Take a break mid-day for a short walk, or move your desk near a window to get the benefits sunlight offers. Artificial sources like a light box can help, too. Always remember to wear sunscreen to protect against damaging rays.

• Keep up your exercise. It may be harder to run or bike ride outdoors with dipping temperatures and snowy surfaces, but indoor exercise can keep the endorphins high to keep your mood happier. Take advantage of the weather and try something new like ice skating or snowshoeing. Even sledding with the kids can get the blood pumping.

• Get your ZZZZs. Your mind and body both need the restoration of a good night’s sleep. Sleep helps repair and reset the mind, helping you ward off depression.

• Mind your meals. We may find temporary comfort in carbohydrates and sugary foods, but those can add unnecessary pounds and drag you down in the long run.

• Try relaxation exercises. Yoga, meditation or even keeping a positivity or gratitude journal can boost your mental outlook.

• Stay connected. If you can’t gather in person, FaceTime and Zoom are great options to stay in touch with friends and family.

If you’re still struggling with Seasonal Affective Disorder, click here for more help:

https://intranet.hartfordhealthcare.org/colleague-support/colleague-well-being

State Exhibit Examines History of Mental Health

Kate Carey-Trull

The Connecticut Historical Society is hosting a unique exhibit focused on the history of mental health treatment in Connecticut and nationwide, including displays about the Institute of Living.

Hartford HealthCare colleagues can get a free ticket to “Common Struggle, Individual Experience: An Exhibition about Mental Health,” which is on display through Oct. 15, 2022, in the group’s Hartford galleries.

The exhibit explores how society has sought to care for the mind and mental health. Letters, photographs and other artifacts help showcase the experience from the past, and oral history interviews, recorded in 2020 and 2021, share modern perspectives. During the course of exhibit, Behavioral Health Network experts will join panel discussions and community education events.

“This is a natural partnership,” said Dr. John Santopietro, senior vice president, Hartford HealthCare, physician–in–chief of the Behavioral Health Network, which includes the Institute of Living. “The fact that the Institute of Living is celebrating its 200th anniversary at the same time that the Connecticut Historical Society is offering this exhibition is such an extraordinary confluence of events. The Institute of Living is a big part of the history of mental health, and a big part of this exhibition.”

On the IOL campus, Annetta Caplinger, vice president of operations, said anniversary plans include partnering with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra, producing a podcast series, and a variety of forums and events.

To get your free ticket to the exhibit, just show your HHC badge at the entrance.

Steve Coates from Marketing Communications toured the exhibit and created a podcast about it at: https://hartfordhealthcare.org/media/podcasts

Head’s Up for Nature’s Grandeur

Robin Stanley

Even the trees at the Institute of Living have a story thanks to vision of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted who designed the grounds to feature dozens of rare and novel species. The park-like landscape offers meandering walkways and quiet, shady corners. Arborists often take tours of the property to marvel at the specimens.

You can take your own self-guided walking tour of the property, following the directions and learning about the trees detailed here.

Please respect the privacy of patients by avoiding photos on the grounds and exploring quietly. The trail is meant to provide a peaceful place for all to roam.